Designing at the Seams

January 10, 2018

Written By:

Phil Dirkse | Area Lead - Advanced Product Development

The Value of Risk Mitigation

As a Product Development Engineer engaged in the automotive industry pre- and post-launch, my daily activities often consist of addressing current production issues and identifying and mitigating future risks. The value of risk mitigation is what I’d like to focus on in this blog. Perhaps this topic won’t rack up thousands of page views in Google analytics but bear with me for a moment. Being able to consistently identify potential failure modes grants designers and engineers future-telling capabilities regarding the success of a new product. It’s almost like having a crystal ball. Risk mitigation is an integral component of effective product development and cannot be overlooked.

The Value of Risk Mitigation

Companies that mitigate risk well find few surprises during product launch because they have already planned and prepared solutions to potential issues. The end result is a product that is thoroughly understood by both consumers and manufacturers. Traction in the market is quicker and costs are reduced with fewer post-launch production changes.

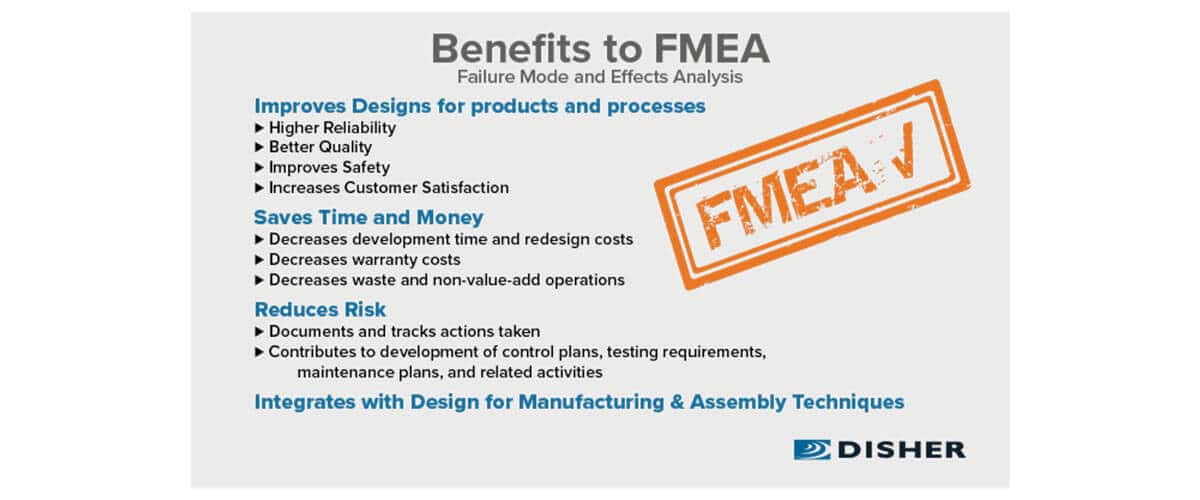

Prior to launch, engineers utilize analysis tools to brainstorm potential problems that could arise during launch. No tool is more thorough and encompassing than a Failure Mode and Effects Analysis, or FMEA. For those who know it, the acronym likely stirs up a range of emotions from dread to anxiety. FMEA focuses on three key criteria: (1) the likelihood of the risk occurring, (2) the ability to detect that the problem has occurred, and (3) the severity of the risk should it occur. The product of these three criteria form the Risk Priority Number, or RPN, which is used to prioritize potential pitfalls.

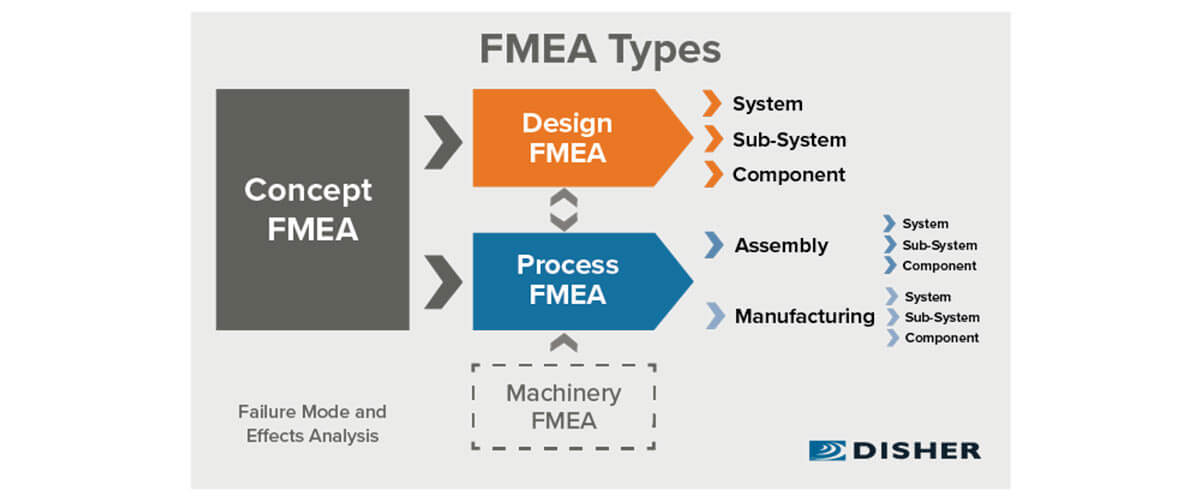

FMEA studies come in two primary flavors: a Design-FMEA and a Process-FMEA. Both are a type of weighted-decision matrix where options are weighted and ranked based on a set of relevant criteria.

Design FMEA

A DFMEA is typically generated during the design review phase and follows a product on through each phase of production. It evolves as new information arises through lessons learned. It explores analyzes things like: material properties, geometries, tolerances, component interfaces, environments, user profiles, degradation, and system interactions. The challenge of a DFMEA lies in the application. If a design team fails to identify a potential issue, there can be no accounting for the impact it might have on a product. When you consider the countless variables involved in even the simplest manufacturing methods and the complexity of the environment in which a product performs, it is easy to understand how a potential issue could go undocumented.

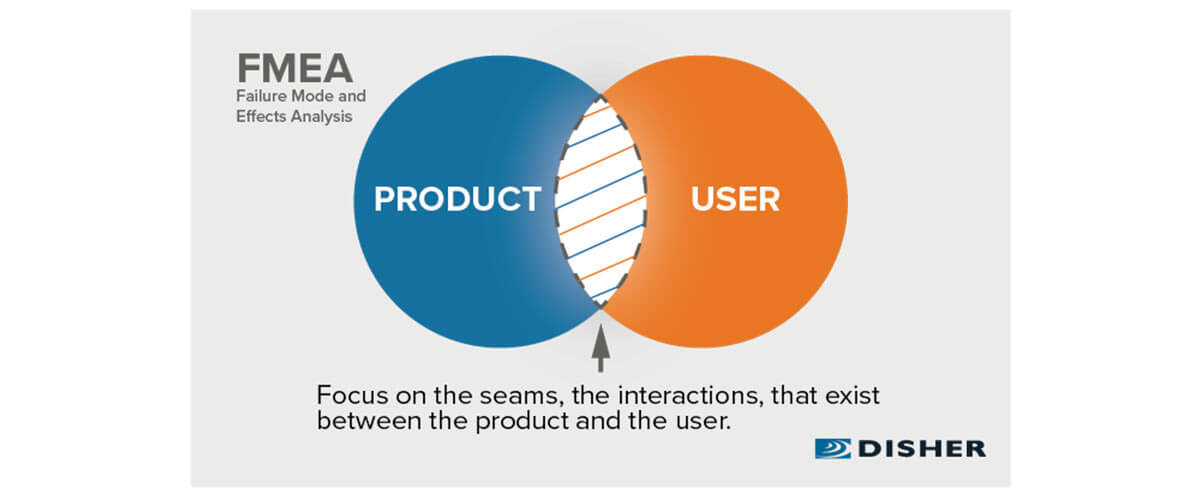

In order to identify all potential failure modes, I find it helpful to study all interactions between the product and the hands of those who touch it. This includes both manufacturers and end users. During a value-stream mapping activity, these interactions show up as “seams” between different parties. These seams are precisely where a wise engineer focuses their attention. A product rarely fails while resting on a table; it fails in the hands of its user. Similarly, raw materials hide their flaws until they are formed and shaped. Even the most basic products, when considered within a real-world environment, become part of a complex system.

Process FMEA

The second type of FMEA is the Process-FMEA which often includes less technical failure modes and can be applied to organizations of any size. PFMEA can be applied to project management as well as product development. It usually focuses on human factors, methods followed while processing, materials used, machines used, measurement systems, and environmental factors. In applying a PFMEA, I find it similarly helpful to focus on these same seams. Depending on the size of the project team and organizational structure, these seams can form between individual employees or entire divisions of a company. In today’s economic environment it is not uncommon to have project teams made up of multiple different suppliers, each providing a subcomponent to an OEM or Tier 1 supplier. Regardless of what the organizational chart looks like, it is at these seams where information and deliverables pass hands, and where the greatest risk of failure exists.

Focus on the Seams

I often hear the term “seamless communication” used when describing efficient teams. To mitigate risk; however, the better framework does not attempt to hide or eliminate the seams. Instead the seams are highlighted while focusing on creating good routines and rhythms for communication. Whether your day-to-day activities involve launching new products or managing particularly complex project teams, there are measurable benefits to be realized from identifying and understanding potential failure modes. Regardless of the tool used to quantify these risks, I encourage you to focus on the interactions – the seams – that exist between product and user.

The team at DISHER would love to learn more about your specific project development needs and help you identify and address potential risks. Let us know how we can best serve you on your next project.

Written By: Phil Dirkse, Product Development Engineer

Phil is a graduate of Franklin W. Olin College of Engineering where he received a BS in Mechanical Engineering. Phil has several patents under his belt relating to renewable energy, and he’s written STEM curriculum for Michigan school districts using community projects as authentic learning opportunities. Phil is an avid sailor who races locally on Lake Michigan and holds a 50-ton Masters License with the USCG.